Le bureau du Directeur des Poursuites Publiques (DPP) a déposé le vendredi 22 novembre dix-huit points d'appel pour contester la décision de la Cour intermédiaire de rayer les vingt-trois accusations contre Navin Ramgoolam dans l’affaire des coffres-forts.

Les magistrats Pranay Sewpal et Navina Parsuramen, avaient statué dans leur «ruling» que les 23 accusations retenues contre l’ancien Premier ministre étaient «incertaines de manière flagrante».

Dans ses points d’appel, le DPP estime que la Cour intermédiaire s’est trompée en statuant que les accusations étaient «vagues». « Les magistrats ont commis une erreur en concluant que l'identité du payeur était un fait matériel à prouver », estime le DPP. Ce dernier ajoute que la cour intermédiaire s’est aussi trompée en rayant les accusations en l’absence de preuves concrètes de préjudices envers Navin Ramgoolam.

De plus, soutient le DPP, la Cour intermédiaire «a eu tort» de statuer que les détails fournis dans l'acte d'accusation contre Navin Ramgoolam «n'étaient pas suffisamment détaillés et pas assez précis». Pour le DPP, les magistrats «ont eu tort de rejeter les accusations, après avoir présumé de la solidité du dossier de l'accusation et du fait que le payeur soit indisponible avant même d'avoir entendu des preuves».

Le leader du Parti travailliste était poursuivi sous la Financial Intelligence and Anti-Money Laundering Act (FIAMLA) de 2002 pour avoir accepté des paiements en espèces supérieurs à la limite autorisée, soit de Rs 500 000. Il était alors poursuivi pour le délit de « limitation of payment in cash ». Navin Ramgoolam aurait, selon l’acte d’accusation, accepté Rs 63,8 millions en espèces en six ans, soit du 31 janvier 2009 au 7 février 2015. La Cour intermédiaire avait rayé les accusations suivant un point de droit de ses avocats.

Ci-dessous, les dix-huit points d'appel du DPP :

- The learned Magistrates erred in holding that the identity of the payer was a material circumstance, under section 125 of the District and Intermediate Courts (Criminal Jurisdiction) Act, which had to be averred and proved.

- The learned Magistrates erred in finding that the information was not sufficiently particularised and did not meet the tests of certainty and precision.

- The learned Magistrates wrongly found that the particulars did not sufficiently provide reasonable information as to the nature of the charge under section 5 of the Financial Intelligence and Anti-Money Laundering Act.

- The learned Magistrates utterly failed to appreciate that the identity of the payer does not relate to the conduct constituting the commission of the office charged and therefore need not be averred (or provided as particulars upon demand) and proved by the prosecution.

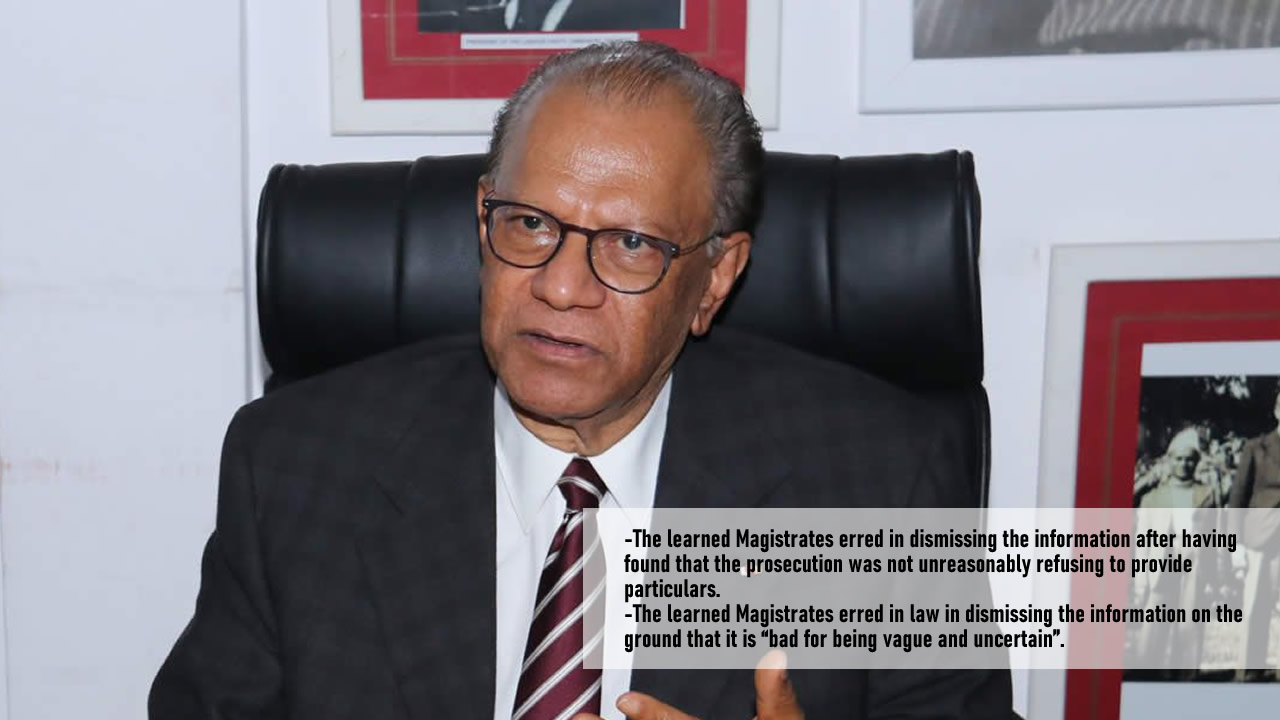

- The learned Magistrates erred in dismissing the information after having found that the prosecution was not unreasonably refusing to provide particulars.

- The learned Magistrates erred in law in dismissing the information on the ground that it is “bad for being vague and uncertain”.

- The learned Magistrates, having wrongly concluded that the particulars did not meet the requirements of section 125 of the District and Intermediate Courts (Criminal Jurisdiction) Act and section 17 of the Criminal Procedure Act, consequently erred in finding that the accused would be unfairly prejudiced in the preparation of his defence.

- The learned Magistrates wrongly concluded that the identity of the payer was essential to inform the accused in detail of the nature of the charge in breach of section 10 (2)(b) of the Constitution.

- The learned Magistrates were wrong to have found that the prosecution’s case was reduced to one of mere possession of money.

- The learned Magistrates wrongly dismissed the charges ex facie the information and in the absence of any concrete evidence of material prejudice.

- The learned Magistrates wrongly found that the accused would be deprived of his right to cross-examination and that “the light of truth may never break through” inasmuch as these findings were not based on evidence, were premature and irrelevant at that stage of proceedings.

- The learned Magistrates were wrong to dismiss the information after having arbitrarily surmised on the strength of the prosecution’s case and the implications of the unavailability of the payer before even hearing any evidence.

- The learned Magistrates failed to consider that the element of ‘accepting payment’ could also be proved by other evidence and not by solely calling the payer to depose.

- The learned Magistrates failed to appreciate properly that the particulars already described the material circumstances of the offence and also failed to appreciate the nature of the offence and the significance of disclosure of the brief to the accused.

- The learned Magistrates were wrong to “imagine the intractable problem being faced by the accused in preparing his defence to be able to meet the prosecution’s case”. Such a finding should not be left to the imagination but should rather be based on evidence.

- The learned Magistrates wrongly held that further particulars were needed to enable the accused to put up a defence, particularly, that of exempt transaction.

- The learned Magistrates failed to appreciate that the absence of the identity of the payer would not prevent the accused from determining if the transactions were exempt pursuant to section 2 of the Financial Intelligence and Anti-Money Laundering Act.

- The learned Magistrates failed to appreciate that the onus of proof, under section 5 of the Financial Intelligence and Anti-Money Laundering Act, rests on the accused with regard to the statutory defence of exempt transaction.

Voici le «ruling» de la Cour intermédiaire dans l'affaire des coffres-forts :

J'aime

J'aime